I don’t usually reblog or post others post in here. But this is something EVERYONE should be aware of.

An advanced piece of malware, known as Regin Malware, has been used in systematic spying campaigns against a range of international targets since at least 2008. A back door-type Trojan, Regin Malware is a complex piece of malware whose structure displays a degree of technical competence rarely seen. Customizable with an extensive range of capabilities depending on the target, it provides its controllers with a powerful framework for mass surveillance and has been used in spying operations against government organizations, infrastructure operators, businesses, researchers, and private individuals.

It is likely that its development took months, if not years, to complete and its authors have gone to great lengths to cover its tracks. Its capabilities and the level of resources behind Regin Malware indicate that it is one of the main cyberespionage tools used by a nation state.

It’s unknown exactly when the first samples of Regin Malware were created. Some of them have timestamps dating back to 2003.

The victims of Regin Malware fall into the following categories:

- Telecom operators

- Government institutions

- Multi-national political bodies

- Financial institutions

- Research institutions

- Individuals involved in advanced mathematical/cryptographical research

So far, we’ve observed two main objectives from the attackers:

- Intelligence gathering

- Facilitating other types of attacks

While in most cases, the attackers were focused on extracting sensitive information, such as e-mails and documents, we have observed cases where the attackers compromised telecom operators to enable the launch of additional sophisticated attacks. More about this in the GSM Targeting section below.

Perhaps one of the most publicly known victims of Regin Malware is Jean Jacques Quisquater (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Jacques_Quisquater), a well-known Belgian cryptographer. In February 2014, Quisquater announced he was the victim of a sophisticated cyber intrusion incident. We were able to obtain samples from the Quisquater case and confirm they belong to the Regin Malware platform.

Another interesting victim of Regin Malware is a computer we are calling “The Magnet of Threats“. This computer belongs to a research institution and has been attacked by Turla, Mask/Careto, Regin Malware, Itaduke, Animal Farm and some other advanced threats that do not have a public name, all co-existing happily on the same computer at some point.

Initial compromise and lateral movement

The exact method of the initial compromise remains a mystery, although several theories exist, which include man-in-the-middle attacks with browser zero-day exploits. For some of the victims, we observed tools and modules designed for lateral movement. So far, we have not encountered any exploits. The replication modules are copied to remote computers by using Windows administrative shares and then executed. Obviously, this technique requires administrative privileges inside the victim’s network. In several cases, the infected machines were also Windows domain controllers. Targeting of system administrators via web-based exploits is one simple way of achieving immediate administrative access to the entire network.

The Regin Malware platform

In short, Regin Malware is a cyber-attack platform which the attackers deploy in the victim networks for ultimate remote control at all possible levels.

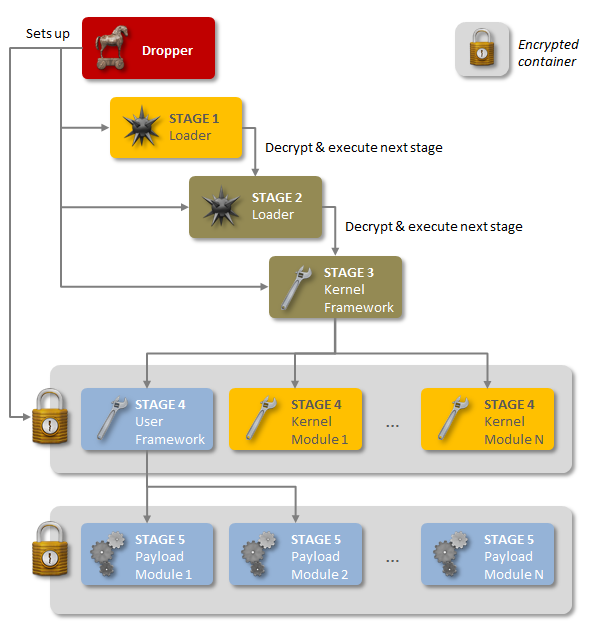

The platform is extremely modular in nature and has multiple stages.

The second stage has multiple purposes and can remove the Regin Malware infection from the system if instructed so by the 3rd stage.

The second stage also creates a marker file that can be used to identify the infected machine. Known filenames for this marker are:

- %SYSTEMROOT%\system32\nsreg1.dat

- %SYSTEMROOT%\system32\bssec3.dat

- %SYSTEMROOT%\system32\msrdc64.dat

Stage 3 exists only on 32 bit systems – on 64 bit systems, stage 2 loads the dispatcher directly, skipping the third stage.

Stage 4, the dispatcher, is perhaps the most complex single module of the entire platform. The dispatcher is the user-mode core of the framework. It is loaded directly as the third stage of the 64-bit bootstrap process or extracted and loaded from the VFS as module 50221 as the fourth stage on 32-bit systems.

The dispatcher takes care of the most complicated tasks of the Regin Malware platform, such as providing an API to access virtual file systems, basic communications and storage functions as well as network transport sub-routines. In essence, the dispatcher is the brain that runs the entire platform.

A thorough description of all malware stages can be found in our full technical paper.

As outlined in a new technical whitepaper from Symantec, Backdoor.Regin is a multi-staged threat and each stage is hidden and encrypted, with the exception of the first stage. Executing the first stage starts a domino chain of decryption and loading of each subsequent stage for a total of five stages. Each individual stage provides little information on the complete package. Only by acquiring all five stages is it possible to analyze and understand the threat.

Figure: Regin Malware’s five stages

Regin Malware also uses a modular approach, allowing it to load custom features tailored to the target. This modular approach has been seen in other sophisticated malware families such as Flamer and Weevil (The Mask), while the multi-stage loading architecture is similar to that seen in the Duqu/Stuxnet family of threats.

Virtual File Systems (32/64-bit)

The most interesting code from the Regin Malware platform is stored in encrypted file storages, known as Virtual File Systems (VFSes).

During our analysis we were able to obtain 24 VFSes, from multiple victims around the world. Generally, these have random names and can be located in several places in the infected system. For a full list, including format of the Regin Malware VFSes, see our technical paper.

Unusual modules and artifacts

With high-end APT groups such as the one behind Regin, mistakes are very rare. Nevertheless, they do happen. Some of the VFSes we analyzed contain words which appear to be the respective codenames of the modules deployed on the victim:

- legspinv2.6 and LEGSPINv2.6

- WILLISCHECKv2.0

- HOPSCOTCH

Another module we found, which is a plugin type 55001.0 references another codename, which is U_STARBUCKS:

GSM Targeting

The most interesting aspect we found so far about Regin Malware is related to an infection of a large GSM operator. One VFS encrypted entry we located had internal id 50049.2 and appears to be an activity log on a GSM Base Station Controller.

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Base_station_subsystem

According to the GSM documentation (http://www.telecomabc.com/b/bsc.html): “The Base Station Controller (BSC) is in control of and supervises a number of Base Transceiver Stations (BTS). The BSC is responsible for the allocation of radio resources to a mobile call and for the handovers that are made between base stations under his control. Other handovers are under control of the MSC.”

Here’s a look at the decoded Regin Malware GSM activity log:

This log is about 70KB in size and contains hundreds of entries like the ones above. It also includes timestamps which indicate exactly when the command was executed.

The entries in the log appear to contain Ericsson OSS MML (Man-Machine Language as defined by ITU-T) commands.

Here’s a list of some commands issued on the Base Station Controller, together with some of their timestamps:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

|

2008–04–25 11:12:14: rxmop:moty=rxotrx;

2008–04–25 11:58:16: rxmsp:moty=rxotrx;

2008–04–25 14:37:05: rlcrp:cell=all;

2008–04–26 04:48:54: rxble:mo=rxocf–170,subord;

2008–04–26 06:16:22: rxtcp:MOty=RXOtg,cell=kst022a;

2008–04–26 10:06:03: IOSTP;

2008–04–27 03:31:57: rlstc:cell=pty013c,state=active;

2008–04–27 06:07:43: allip:acl=a2;

2008–04–28 06:27:55: dtstp:DIP=264rbl2;

2008–05–02 01:46:02: rlstp:cell=all,state=halted;

2008–05–08 06:12:48: rlmfc:cell=NGR035W,mbcchno=83&512&93&90&514&522,listtype=active;

2008–05–08 07:33:12: rlnri:cell=NGR058y,cellr=ngr058x;

2008–05–12 17:28:29: rrtpp:trapool=all;

|

Descriptions for the commands:

- rxmop – check software version type;

- rxmsp – list current call forwarding settings of the Mobile Station;

- rlcrp – list off call forwarding settings for the Base Station Controller;

- rxble – enable (unblock) call forwarding;

- rxtcp – show the Transceiver Group of particular cell;

- allip – show external alarm;

- dtstp – show DIgital Path (DIP) settings (DIP is the name of the function used for supervision of the connected PCM (Pulse Code Modulation) lines);

- rlstc – activate cell(s) in the GSM network;

- rlstp – stop cell(s) in the GSM network;

- rlmfc – add frequencies to the active broadcast control channel allocation list;

- rlnri – add cell neightbour;

- rrtpp – show radio transmission transcoder pool details;

The log seems to contain not only the executed commands but also usernames and passwords of some engineering accounts:

sed[snip]:Alla[snip] hed[snip]:Bag[snip] oss:New[snip] administrator:Adm[snip] nss1:Eric[snip]

In total, the log indicates that commands were executed on 136 different cells. Some of the cell names include “prn021a, gzn010a, wdk004, kbl027a, etc…“. The command log we obtained covers a period of about one month, from April 25, 2008 through May 27, 2008. It is unknown why the commands stopped in May 2008 though; perhaps the infection was removed or the attackers achieved their objective and moved on. Another explanation is that the attackers improved or changed the malware to stop saving logs locally and that’s why only some older logs were discovered.

Communication and C&C

The C&C mechanism implemented in Regin Malware is extremely sophisticated and relies on communication drones deployed by the attackers throughout the victim networks. Most victims communicate with another machine in their own internal network, through various protocols, as specified in the config file. These include HTTP and Windows network pipes. The purpose of such a complex infrastructure is to achieve two goals: give attackers access deep into the network, potentially bypassing air gaps and restrict as much as possible the traffic to the C&C.

Here’s a look at the decoded configurations:

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

17.3.40.101 transport 50037 0 0 y.y.y.5:80 ; transport 50051 217.y.y.yt:443

17.3.40.93 transport 50035 217.x.x.x:443 ; transport 50035 217.x.x.x:443

50.103.14.80 transport 27 203.199.89.80 ; transport 50035 194.z.z.z:8080

51.9.1.3 transport 50035 192.168.3.3:445 ; transport 50035 192.168.3.3:9322

18.159.0.1 transport 50271 DC ; transport 50271 DC

|

In the above table, we see configurations extracted from several victims that bridge together infected machines in what appears to be virtual networks: 17.3.40.x, 50.103.14.x, 51.9.1.x, 18.159.0.x. One of these routes reaches out to the “external” C&C server at 203.199.89.80.

The numbers right after the “transport” indicate the plugin that handles the communication. These are in our case:

- 27 – ICMP network listener using raw sockets

- 50035 – Winsock-based network transport

- 50037 – Network transport over HTTP

- 50051 – Network transport over HTTPS

- 50271 – Network transport over SMB (named pipes)

The machines located on the border of the network act as routers, effectively connecting victims from inside the network with C&Cs on the internet.

After decoding all the configurations we’ve collected, we were able to identify the following external C&Cs.

| C&C server IP | Location | Description |

| 61.67.114.73 | Taiwan, Province Of China Taichung | Chwbn |

| 202.71.144.113 | India, Chetput | Chennai Network Operations (team-m.co) |

| 203.199.89.80 | India, Thane | Internet Service Provider |

| 194.183.237.145 | Belgium, Brussels | Perceval S.a. |

One particular case includes a country in the Middle East. This case was mind-blowing so we thought it’s important to present it. In this specific country, all the victims we identified communicate with each other, forming a peer-to-peer network. The P2P network includes the president’s office, a research center, educational institution network and a bank.

These victims spread across the country are all interconnected to each other. One of the victims contains a translation drone which has the ability to forward the packets outside of the country, to the C&C in India.

This represents a rather interesting command-and-control mechanism, which is guaranteed to raise very little suspicions. For instance, if all commands to the president’s office are sent through the bank’s network, then all the malicious traffic visible for the president’s office sysadmins will be only with the bank, in the same country.

Victim Statistics

Over the past two years, we collected statistics about the attacks and victims of Regin Malware. These were aided by the fact that even after the malware is uninstalled, certain artifacts are left behind which can help identify an infected (but cleaned) system. For instance, we’ve seen several cases where the systems were cleaned but the “msrdc64.dat” infection marker was left behind.

So far, victims of Regin Malware were identified in 14 countries:

- Algeria

- Afghanistan

- Belgium

- Brazil

- Fiji

- Germany

- Iran

- India

- Indonesia

- Kiribati

- Malaysia

- Pakistan

- Russia

- Syria

In total, we counted 27 different victims, although it should be pointed out that the definition of a victim here refers to a full entity, including their entire network. The number of unique PCs infected with Regin Malware is of course much, much higher.

From the map above, Fiji and Kiribati are unusual, because we rarely see such advanced malware in such remote, small countries. In particular, the victim in Kiribati is most unusual. To put this into context, Kiribati is a small island in the Pacific, with a population around 100,000.

Attribution

Considering the complexity and cost of Regin Malware development, it is likely that this operation is supported by a nation-state. While attribution remains a very difficult problem when it comes to professional attackers such as those behind Regin Malware, certain metadata extracted from the samples might still be relevant.

As this information could be easily altered by the developers, it’s up to the reader to attempt to interpret this: as an intentional false flag or a non-critical indicator left by the developers.

Timeline and target profile

Regin Malware infections have been observed in a variety of organizations between 2008 and 2011, after which it was abruptly withdrawn. A new version of the malware resurfaced from 2013 onwards. Targets include private companies, government entities and research institutes. Almost half of all infections targeted private individuals and small businesses. Attacks on telecoms companies appear to be designed to gain access to calls being routed through their infrastructure.

Figure: Confirmed Regin infections by sector

Infections are also geographically diverse, having been identified in mainly in ten different countries.

Figure: Confirmed Regin Infections by country

Infection vector and payloads

The infection vector varies among targets and no reproducible vector had been found at the time of writing. Symantec believes that some targets may be tricked into visiting spoofed versions of well-known websites and the threat may be installed through a Web browser or by exploiting an application. On one computer, log files showed that Regin Malware originated from Yahoo! Instant Messenger through an unconfirmed exploit.

Regin Malware uses a modular approach, giving flexibility to the threat operators as they can load custom features tailored to individual targets when required. Some custom payloads are very advanced and exhibit a high degree of expertise in specialist sectors, further evidence of the level of resources available to Regin’s authors.

There are dozens of Regin Malware payloads. The threat’s standard capabilities include several Remote Access Trojan (RAT) features, such as capturing screenshots, taking control of the mouse’s point-and-click functions, stealing passwords, monitoring network traffic, and recovering deleted files.

More specific and advanced payload modules were also discovered, such as a Microsoft IIS web server traffic monitor and a traffic sniffer of the administration of mobile telephone base station controllers.

Stealth

Regin Malware’s developers put considerable effort into making it highly inconspicuous. Its low key nature means it can potentially be used in espionage campaigns lasting several years. Even when its presence is detected, it is very difficult to ascertain what it is doing. Symantec was only able to analyze the payloads after it decrypted sample files.

It has several “stealth” features. These include anti-forensics capabilities, a custom-built encrypted virtual file system (EVFS), and alternative encryption in the form of a variant of RC5, which isn’t commonly used. Regin Malware uses multiple sophisticated means to covertly communicate with the attacker including via ICMP/ping, embedding commands in HTTP cookies, and custom TCP and UDP protocols.

Conclusions

Regin Malware is a highly-complex threat which has been used in systematic data collection or intelligence gathering campaigns. The development and operation of this malware would have required a significant investment of time and resources, indicating that a nation state is responsible. Its design makes it highly suited for persistent, long term surveillance operations against targets.

The discovery of Regin Malware highlights how significant investments continue to be made into the development of tools for use in intelligence gathering. Symantec believes that many components of Regin remain undiscovered and additional functionality and versions may exist. Additional analysis continues and Symantec will post any updates on future discoveries

For more than a decade, a sophisticated group known as Regin Malware has targeted high-profile entities around the world with an advanced malware platform. As far as we can tell, the operation is still active, although the malware may have been upgraded to more sophisticated versions. The most recent sample we’ve seen was from a 64-bit infection. This infection was still active in the spring of 2014.

The name Regin Malware is apparently a reversed “In Reg”, short for “In Registry”, as the malware can store its modules in the registry. This name and detections first appeared in anti-malware products around March 2011.

From some points of view, the platform reminds us of another sophisticated malware: Turla. Some similarities include the use of virtual file systems and the deployment of communication drones to bridge networks together. Yet through their implementation, coding methods, plugins, hiding techniques and flexibility, Regin Malware surpasses Turla as one of the most sophisticated attack platforms we have ever analysed.

The ability of this group to penetrate and monitor GSM networks is perhaps the most unusual and interesting aspect of these operations. In today’s world, we have become too dependent on mobile phone networks which rely on ancient communication protocols with little or no security available for the end user. Although all GSM networks have mechanisms embedded which allow entities such as law enforcement to track suspects, there are other parties which can gain this ability and further abuse them to launch other types of attacks against mobile users.

Further reading

- Indicators of compromise for security administrators and more detailed and technical information can be found in our technical paper – Regin: Top-tier espionage tool enables stealthy surveillance

- Full technical paper with IOCs.

- Kaspersky products detect modules from the Regin platform as: Trojan.Win32.Regin.gen and Rootkit.Win32.Regin.

Source

- Symantec Official Blog: Regin: Top-tier espionage tool enables stealthy surveillance

- SecureList/Kaspersky Lab: Regin: Nation-state ownage of GSM networks

Protection information

- Symantec and Norton products detect this threat as Backdoor.Regin.

- More information about Regin is available to Kaspersky Intelligent Services’ clients. Contact: intelreports@kaspersky.com

Disclaimer:

Date: 20141125:15:05hrs.

This post was taken from Symantec Official Blog and SecureList post as mentioned in the sources list. If you suspect you might be a victim, you should contact them directly with as much technical details as possible.

blackMORE Ops Learn one trick a day ….

blackMORE Ops Learn one trick a day ….