- Version 2.0 – 17-06-2015

- – Improved: Added title and version history.

- – Improved: Added /srv, /media and /proc.

- – Improved: Updated descriptions to reflect modern Linux File Systems.

- – Fixed: Multiple typo’s.

- – Fixed: Appearance and colour.

- Version 1.0 – 14-02-2015

- – Created: Initial diagram.

- – Note: Discarded lowercase version.

[/box]

What is a file in Linux?

A simple description of the UNIX system, also applicable to Linux, is this:

On a UNIX system, everything is a file; if something is not a file, it is a process.

This statement is true because there are special files that are more than just files (named pipes and sockets, for instance), but to keep things simple, saying that everything is a file is an acceptable generalization. A Linux system, just like UNIX, makes no difference between a file and a directory, since a directory is just a file containing names of other files. Programs, services, texts, images, and so forth, are all files. Input and output devices, and generally all devices, are considered to be files, according to the system.

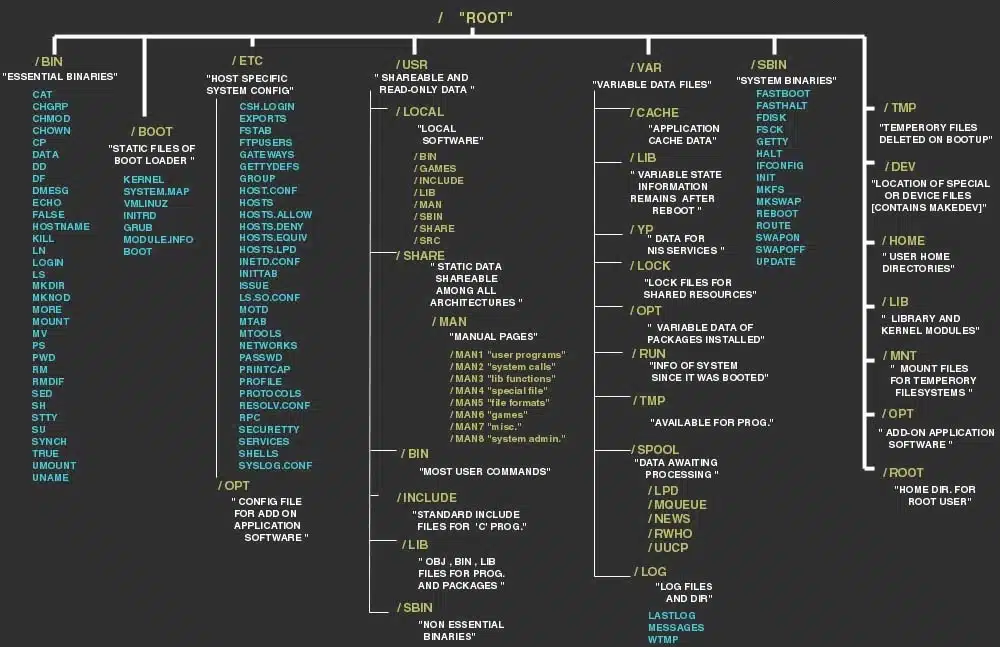

In order to manage all those files in an orderly fashion, man likes to think of them in an ordered tree-like structure on the hard disk, as we know from MS-DOS (Disk Operating System) for instance. The large branches contain more branches, and the branches at the end contain the tree’s leaves or normal files. For now we will use this image of the tree, but we will find out later why this is not a fully accurate image.

| Directory | Description |

|---|---|

|

Primary hierarchy root and root directory of the entire file system hierarchy. |

|

Essential command binaries that need to be available in single user mode; for all users, e.g., cat, ls, cp. |

|

Boot loader files, e.g., kernels, initrd. |

|

Essential devices, e.g., /dev/null. |

|

Host-specific system-wide configuration filesThere has been controversy over the meaning of the name itself. In early versions of the UNIX Implementation Document from Bell labs, /etc is referred to as the etcetera directory, as this directory historically held everything that did not belong elsewhere (however, the FHS restricts /etc to static configuration files and may not contain binaries). Since the publication of early documentation, the directory name has been re-designated in various ways. Recent interpretations include backronyms such as “Editable Text Configuration” or “Extended Tool Chest”. |

|

Configuration files for add-on packages that are stored in /opt/. |

|

Configuration files, such as catalogs, for software that processes SGML. |

|

Configuration files for the X Window System, version 11. |

|

Configuration files, such as catalogs, for software that processes XML. |

|

Users’ home directories, containing saved files, personal settings, etc. |

|

Libraries essential for the binaries in /bin/ and /sbin/. |

|

Alternate format essential libraries. Such directories are optional, but if they exist, they have some requirements. |

|

Mount points for removable media such as CD-ROMs (appeared in FHS-2.3). |

|

Temporarily mounted filesystems. |

|

Optional application software packages. |

|

Virtual filesystem providing process and kernel information as files. In Linux, corresponds to a procfs mount. |

|

Home directory for the root user. |

|

Essential system binaries, e.g., init, ip, mount. |

|

Site-specific data which are served by the system. |

|

Temporary files (see also /var/tmp). Often not preserved between system reboots. |

|

Secondary hierarchy for read-only user data; contains the majority of (multi-)user utilities and applications. |

|

Non-essential command binaries (not needed in single user mode); for all users. |

|

Standard include files. |

|

Libraries for the binaries in /usr/bin/ and /usr/sbin/. |

|

Alternate format libraries (optional). |

|

Tertiary hierarchy for local data, specific to this host. Typically has further subdirectories, e.g., bin/, lib/, share/. |

|

Non-essential system binaries, e.g., daemons for various network-services. |

|

Architecture-independent (shared) data. |

|

Source code, e.g., the kernel source code with its header files. |

|

X Window System, Version 11, Release 6. |

|

Variable files—files whose content is expected to continually change during normal operation of the system—such as logs, spool files, and temporary e-mail files. |

|

Application cache data. Such data are locally generated as a result of time-consuming I/O or calculation. The application must be able to regenerate or restore the data. The cached files can be deleted without loss of data. |

|

State information. Persistent data modified by programs as they run, e.g., databases, packaging system metadata, etc. |

|

Lock files. Files keeping track of resources currently in use. |

|

Log files. Various logs. |

|

Users’ mailboxes. |

|

Variable data from add-on packages that are stored in /opt/. |

|

Information about the running system since last boot, e.g., currently logged-in users and running daemons. |

|

Spool for tasks waiting to be processed, e.g., print queues and outgoing mail queue. |

|

Deprecated location for users’ mailboxes. |

|

Temporary files to be preserved between reboots. |

Types of files in Linux

Most files are just files, called regular files; they contain normal data, for example text files, executable files or programs, input for or output from a program and so on.

While it is reasonably safe to suppose that everything you encounter on a Linux system is a file, there are some exceptions.

Directories: files that are lists of other files.Special files: the mechanism used for input and output. Most special files are in/dev, we will discuss them later.Links: a system to make a file or directory visible in multiple parts of the system’s file tree. We will talk about links in detail.(Domain) sockets: a special file type, similar to TCP/IP sockets, providing inter-process networking protected by the file system’s access control.Named pipes: act more or less like sockets and form a way for processes to communicate with each other, without using network socket semantics.

File system in reality

For most users and for most common system administration tasks, it is enough to accept that files and directories are ordered in a tree-like structure. The computer, however, doesn’t understand a thing about trees or tree-structures.

Every partition has its own file system. By imagining all those file systems together, we can form an idea of the tree-structure of the entire system, but it is not as simple as that. In a file system, a file is represented by an inode, a kind of serial number containing information about the actual data that makes up the file: to whom this file belongs, and where is it located on the hard disk.

Every partition has its own set of inodes; throughout a system with multiple partitions, files with the same inode number can exist.

- Owner and group owner of the file.

- File type (regular, directory, …)

- Permissions on the file

- Date and time of creation, last read and change.

- Date and time this information has been changed in the inode.

- Number of links to this file (see later in this chapter).

- File size

- An address defining the actual location of the file data.

The only information not included in an inode, is the file name and directory. These are stored in the special directory files. By comparing file names and inode numbers, the system can make up a tree-structure that the user understands. Users can display inode numbers using the -i option to ls. The inodes have their own separate space on the disk.

Totally unrelated to your post, but what program did you use to make the filesystem chart? It’s so easy on the eyes.

Really? I used gimp and then inverted color.

Is this realy true? it looks more like bsd. Like bin should be static binaries for boot use, But for most linux I use (fedora and ubuntu) I think that everything in /usr/bin is linked to /bin or even worse bin is a link to /usr/bin

Hi anders,

The problem is there’s too many standards and then sub-standards. i.e. Unix, Minix, BSD(open, free, net), Debian, Slackrware, RedHat, Arch to name a few … my image least gives an idea (I was mainly concerned about package location, configuration location). Like you’ve mentioned, binaries are now floating all over the place at the mercy of developers and converts from other OS’s….

Thank you for this explanation. I am a linux noob trying to get my lpic and this here helps me alot to understand how everything is related! Kudos to you!

‘Temperory’ under /tmp should be ‘Temporary’?

I wish you’d added a bit about what the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS) http://refspecs.linuxfoundation.org/fhs.shtml is, maintained by the Linux Foundation. Sadly, the FHS is like Rodney Dangerfield in one way: “it don’t get no respect,” although it should. It actually does get some respect, since most major distro’s go along with it more or less in order to enable software developed by different developers to be installed and to work. But it’s in the more and the less where deviations occur and problems crop up for application developers, installers and users. So one more thing to consider when you decide you want to upgrade to a newer, shinier distro is: how closely does the distro’s file system conform to the FHS? Close enough to install everything I want and need?

I’ve taught an intro to Linux course a couple of times. This post is a great short introduction to the Linux file system, and the graphic of the standard file hierarchy is one of the best and clearest I’ve seen. Thanks for creating it.

I figure the file system made sense at one point to somebody but now I always feel like we are stuck with it just like Qwerty keyboards.

There is a utility called ‘tree’ available from most repositories. It will format a list of files and folders in a graphical manner. Options control whether it uses ASCII characters, ASCII drawing characters, or other means to “draw” the output.

“Date and time of creation, last read and change.”

I don’t think Linux keeps “time of creation”.

Indeed, it doesn’t. He probably confused this with the “ctime,” as many people do.

Omg… This should’ve been included in my Uni course.

I’ve created a PDF of this post with bookmarks. If the author is interested in a copy, send me an email and I’d be happy to provide a copy.

I don’t need a copy. I’m happy for you to share the PDF as you see fit under Creative Commons license for educational purposes.

I would appreciate if you just put a link somewhere to this website for the work I’ve done.. entirely upto you. Cheers,

-BMO

noob sure2

2 (conflicting) entries for /bin ? No reference that what goes into /sbin should (must ?) be statically compiled ? And, somewhere, a note about if it can(‘t) be a filesystem mount point.

By the way “/usr” means “Unix System Resource”

If my understanding is correct, that’s Unix FS explanation. Linux, I guess somewhat evolved and bended those meanings.